The Plain of Jars

During 1959-1972 communist North-Vietnam did not implement the agreement that was signed and instead used the Lao territory as a path to fighting war in South-Vietnam, supported the Lao communists in fiercely attacking military posts of the neutral Lao Government (presided by Prince Souvanna Phouma) in MR-II, MR-III and MR-IV. This is was partly due to the drastic increase in modern weaponry provided by the Soviet Union to North-Vietnam for use in the Indochina war. This included heavy tanks, light and heavy transportation vehicles, anti-aircraft guns, artilleries of all calibers (86 mm, 122 mm, 130 mm), 122 mm rockets and movable anti-aircraft missile systems equipped with 12.8 mm, 14.6 mm, 25 mm, 37 mm, 57 mm, and 76 mm guns, and MIG aircrafts for the air defense of North-Vietnam and the air fight against the US. The US had to drop bombs on all the roads originating from the China Sea near Hai-Phong and Hanoi. The enemy was equipped with SAM (soil-to-air missiles), which made their military and weaponry power many times stronger than the fighting power of the allies. As a result, MR-II and the rest of the country got under heavy attack from North-Vietnam.

At that time, MR-II had almost two divisions (about 10,000 soldiers) that were assigned for the protection of Xieng Khouang and Houaphan Provinces. All the changes mentioned earlier made it critical for the MR-II Commander to try his best to control communist North-Vietnam’s expansion. Maj. Gen. Vang Pao and military officers in all Lao military regions had to realign the structure of the Royal Lao Army starting in 1970. The kingdom of Laos was divided into five military regions, each of which was equipped with one division, for a total of five divisions countrywide, all receiving support from the US. When it was realized that the enemy had several times more troops and more weapons than the allies, the Vientiane Government had to ask for air support from the US to continually drop bombs on enemy positions and conduct air operations until 1973.

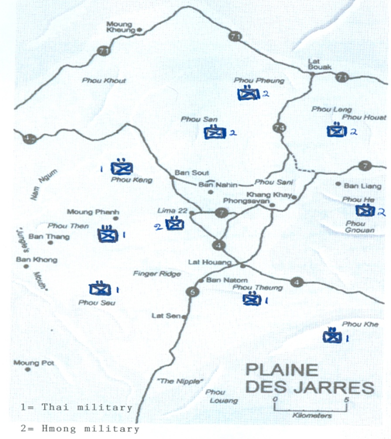

When Gen. Vang Pao received extra air support from the US for MR-II, he decided to lay out plans to launch the second attack against the Plain of Jars. The plan was code-named, “Honor Recovery” Plan. Gen. Vang Pao asked for military support from Thailand for operations in the Long Cheng area because most of the MR-II troops were already busy on the front line. Starting in June 1969, the General’s plan of attack was as follows:

- Front I: push the enemy from Samthong to Louang Mat, Ban Na, Phou Xeu, Muang Phanh and ultimately attack the Plain of Jars,

- Front II: push the enemy toward Muang Soui and after seizing Muang Soui, cleanse the Lat Bouak area — west of the Plain of Jars and communist command center.

The attack of Muang Soui this time around caused the loss of two courageous pilots, Capt. Ly Lue and Lt. Lor Nieng. Ly Lue was the one who gave a lot of hope to Maj. Gen. Vang Pao. He received support from B-52’s, F-4’s, Fantom F111, A1E and T-28’s that made joint sorties to protect his flights; he also got the support from the Thai Army who came to the rescue. The overall attack got fairly good results in that the allies were able to seize the Plain of Jars; destroy artilleries, tanks, ammunition stocks and several thousand of enemy soldiers; use the Plain of Jars as a site of celebration for the 1970 Hmong New Year. Gen. Vang Pao and the Thai military officers laid out firm plans to protect the Plain of Jars, coded-named Plans 163 and 114, including the following troop deployments:

- One Thai battalion to seize Phou Teung and dig a hiding ground hole.

- One battalion to protect Phou Keng and dig a hiding ground hole.

- One Thai battalion to capture Phu Xeu and dig a hiding ground hole.

- OneThai battalion to seize Phou Khae, set up four 155 mm artilleries and four 105 mm artilleries.

- One Thai regiment to station in Muang Phanh, mid-way between Phou Keng and Phou Xeu, with the mission to set the four mountain ranges listed above as support bases.

- One artillery battalion with four 105 mm and four 155 mm guns to station in Muang Phanh and ready to defend allies’s positions in the Plain of Jars.

- Assign two MR-II Hmong battalions to locate enemy targets, monitor enemy mouvements and coordinate air and artilleries operations.

- Station one MR-II Hmong battalion on top of Phou Houat to protect the roads leading to Khang Khay and Lat Bouak.

Photo #129. B-52 dropping bombs on enemy positions

From January to March 1971, the weather started to be cloudy and limited the efficiency of the allies’ air strikes, which in turn made it easier for the enemy to move their vehicles and their troops around. This allowed the enemy to heavily attack the allies everywhere on the ground around the Plain of Jars, including the Hmong troops who monitored their movements. They started attacking all the allies’ mountain positions simultaneously, firing artillery shells and launching rockets to every corner of the battle field, making it impossible for the allies to regroup.

Once the enemy seized several important mountain posts, they started attacking the Thai positions in the Plain of Jars, recaptured that whole area, and pushed the allies out to Long Cheng, making it an abandoned site during the entire 1971 year.

Photo #130. US F-4 Jet providing air support to the Vientiane government and dropping bombs on North-Vietnamese positions

Map #131. “Honor Restoration” War to recapture positions that fell into North-Vietnam’s hands started in July 1969, led to the New Year celebration in May 1970, and seized again by the enemy in March 1971.

Map #131. “Honor Restoration” War to recapture positions that fell into North-Vietnam’s hands started in July 1969, led to the New Year celebration in May 1970, and seized again by the enemy in March 1971.

Map #132. Position layout for the defense of the Plain of Jars in 1970/1971. Battalions #2 were Hmong troops, and Battalions and Regiments #1 were Thai troops. Enemy Divisions 312 and 316 attacked the Plain of Jars and were about to seize Long Cheng that was saved at the last minute by heavy B52 bombing. Long Cheng was saved but stayed vacant for quite some time.

Long Cheng

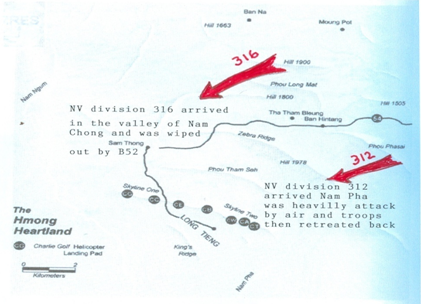

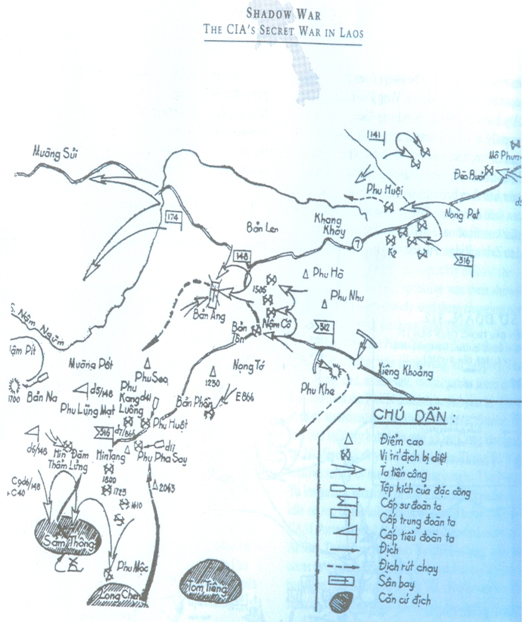

North-Vietnam used two divisions to attack the Plain of Jars. Division 316 and one artillery regiment, equipped with tanks, started their attack from Ban Bane, moving along Highway 7, and then attacked Phou Houat, Phou Keng and the Plain of Jars. Division 312 and several Datcong (dare-devil) battalions moved out from Xieng Khouang along Highway 4, and attacked Phou Teung and Phou Khae. Once they captured the Plain of Jars, the enemy began their cleansing operation of the allied troops –most of whom were Thai soldiers, who did not know their way out and had to fight for their lives and/or get injured. By the beginning of March 1971, once the allies left the Plain of Jars, the enemy pushed them toward Long Cheng, hoping to seize that military camp. Their plan of attack of Long Cheng (see Maps #122 and 113) was as follows:

- Division 316 and one dare-devil battalion attacked from Ban Na (LS15), along the Nam Chong Creek, heading toward the foothill of Phou Pha Thao to cut their eastern supply line. The allies were closely watching the enemy’s movement. When the enemy reached the Nam Chong Creek and were about to climb Mount Pha Thao on their way to Sam Thong, Gen. Vang Pao and Mr. Jerry Daniels asked for two B-52 aircrafts to fly in and drop bombs and F4 to drop CBU bombs on North-Vietnam’s Division 316, and almost eradicating the whole division.

Map #133. North-Vietnam attacked all Gen. Vang Pao’s and Thai troops at the Plain of Jars in February 1971 then pursued the Hmong and Thai troops to Long Cheng but B52 struck them and save Long Tieng.

Map #133. North-Vietnam attacked all Gen. Vang Pao’s and Thai troops at the Plain of Jars in February 1971 then pursued the Hmong and Thai troops to Long Cheng but B52 struck them and save Long Tieng.

Nam Chong was a creek that flows along the foothill of Phou Pha Thao and Phou Pha Chong, on its way to its junction with the Nam Ngum River. Without the B-52 and F4 dropping bombs on the enemy, Long Cheng would have certainly been lost, because the enemy had deployed two army contingents to the area. The more important unit of the two was Division 316, which severely suffered from B-52 bombing while on its way to Sam Thong, trying to cut the allies’ supply line. A high mountain range sits on the western part of the Sam Thong-Long Cheng area and offers many hiding sites. Had the enemy been able to capture this area, it would have been hard to fight it back. Besides, the allies did not have a strong defensive base. Indeed, it B-52 bombing was very timely in cutting off enemy troops.

Division 312 and several dare-devil battalions were split into two groups as follows:

- The first group with heavy weapons and tanks moved in the middle, from Lat Sene-Ban Pha to Phou Louang Matt and to Ban Hinh Tang (LS74).

- The second group was on the allies’ trail, pushing them from Pa Dong (LS05) to Phou Bia, then to Pha Khao (LS14), and finally to Long Cheng.

Part of Division 312 troopers, with tanks and heavy 130 mm, 122 mm and 86 mm heavy artilleries, were pushing from the Plain of Jars, heading toward Hine Tang, Phou Pha Xay, Nam Pha and Pha Khao. They were about to reach Nam Pha when T-28 aircraft and F4 and F111 jets dropped bombs on them. Only one company survived the air raid and was able to reach the top of Phou Rassavang. Another Vietnamese battalion reached Mount Appolo, located on the east side of Long Cheng. The allies fought with that battalion for almost one month, and then left the area because the expected support coming from Sam Thong never arrived. As a result, Long Cheng remained safe.

Map #134. North-Vietnam sent Divisions 316 and 312 to attack Long Cheng and wipe out the Hmong in Military Region II, but when Division 316 arrived at the valley of Nam Chong west of Samthong, B52 wiped it out and saved Long Tieng until May 1975. Division 312 arrived at Nam Pha and also was bombed by F4, Sky Rider and T28. It had to retreat back and sent only guerrilla to attack Long Cheng, which remained an empty town all year in 1971.

Regiment 174 was made up of Pa Chai troopers, and Regiment 141 consisted of mixed North-Vietnamese ethnics. Both regiments were assigned the protection of the newly captured Plain of Jars from Gen. Vang Pao’s troops. Air operations inflicted very heavy damages to the enemy and constituted a source of satisfaction for the allies, as long as they knew how to use those resources and had a good execution plan. The enemy was afraid of B-52’s, F111’s, and bomb dropping by F4’s, Sky Riders, A1E’s and T-28’s. As a result, their plan to capture Long Cheng failed to materialize. The enemy then deployed guerilla raiders from Regiment 866 to destroy several allies’ positions around Long Cheng. These raiders were heavily repulsed each time, and finally retreated. 1971 was the year when the Long Cheng residents had to immigrate to Vientiane, Na Sou, and Ban Sone, leaving Long Cheng as a ghost town during most of that year.

Photo #135. The allied troops seized Phou Keng Mountain, southwest of the Plain of Jars in early 1970 but lost it back to the enemy in March 1971.

Photo #136 Rice bags captured at the Plain of Jars in 1970.

Photo #137 North-Vietnam’s 122 mm artillery captured in 1970

Photo #137 North-Vietnam’s 122 mm artillery captured in 1970

Photo #138. North-Vietnam’s AK guns captured in 1970

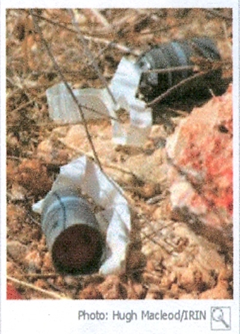

Photo #139 CBU bombs dropped from the air.

Photo #140 Red spots refer to most heavily bombarded areas in MR-II, MR-III and MR-IV during 1968-1972.

Photo #140 Red spots refer to most heavily bombarded areas in MR-II, MR-III and MR-IV during 1968-1972.

Plan to Reconquer The Plain Of JARS

This was Gen. Vang Pao’s third plan to recapture the Plain of Jars. In July 1971, Gen. Vang Pao sent Regiments 21 and 26 by helicopter to Lat Bouak to attack the enemy’s position at Song Hat, Muang Kheung west of the Plain of Jars. He also sent Regiments 22 and 24 to join Regiment 28 at Bouam Long (LS32) by helicopter, with the mission to regain Lat Bouak and cut the enemy’s supply line. After landing on the ground, Regiments 21 and 26 fought with the enemy for about three weeks and then ran into problems—many of their troopers developed blistering feet and could not walk. The causes of the blistering were unknown, some of which might included the following:

- Troopers were wearing shoes made in Taiwan that might have chemically contaminated rubber component. Those not wearing the same Taiwanese shoes appeared not to have any blisters and no other problems.

- In retrospective, these blisters might have been caused by the remains of the bombs that were dropped all over around the Plain of Jars. Maybe, the bombs contained chemical elements that caused the blistering. Regiments 21 and 26 soldiers used to walk along areas subject to heavy precipitations that made shoes wet. The Plain of Jars was probably the most intensely bombarded region in the whole world.

For those reasons, Regiments 21 and 26 had to pull out of the area. Many of the soldiers were pursued by tanks and some of them drowned in the Nam Ngum River –this was during the raining season, with fast flowing flows and under heavy tank pursuit. To evade the tanks, some had to cross the river and drowned. Once Regiments 21 and 26 retreated, Regiments 22 and 24 were the subject of heavy enemy attacks and had to retreat to Bouam Long.

The Fourth Plain of Jars Attack by Gen. Vang Pao

In June 1972, Gen.Vang Pao sent Division II along with one Thai regiment and two Lao regiments from MR-III (Regiments 33 and 35) to attack the enemy in the Plain of Jars. The mission of the Thai regiemtn was to be ready to reoccupy the newly recaptured positions. Division II made the following deployments:

- Regiments 21, 23, 26 and 35 to enter Khang Kho (LS204), push the enemy toward Lat Sene and ultimately recapture the Plain of Jars.

- Regiment 33 to seize Phou Pha Xay.

- Regiments 22 and 24 to cut off enemy supply lines along Highway 7 between Kahng Khay and Ban Bane (Muang Kham).

Those operations had not yet allowed the allies to recapture the Plain of Jars; they only involved attacking several enemy positions around the Plain of Jars. The operations were called off due to the cease-fire agreement signed by the US and North-Vietnam in Paris, France on January 27, 1973. From that point on, Division II Commander got the order to assure security at Sala Phou Khoune Camp, at the junction of Highways 13 (heading to Vientiane) and 7 (heading to Phou Nong Phi, the Plain of Jars, and North-Vietnam). From Division II, one regiment was assigned the mission to control the area between Ban Na (LS15), Phou Pha Xay, Pa Dong (LS05), and Khang Kho (LS204); two regiments to secure Bouam Long Camp (LS32); and one regiment, to secure Muang Mork (LS46). The overall objective was then to protect the allies-occupied territories from enemy penetration. No matter how the protection was performed, it was still useless because once the US and North-Vietnam signed their cease-fire agreement, the Royal Lao Army ran out of supporters.

Photo #141. Ban Sone near LS272 in 1973

When the situation became more insecure, the North-Vietnamese and Lao communist troops took advantage of it by attacking several Vientiane military positions, including the command center of Division II at Sala Phou Khoune, Muang Mork, and many positions around Long Cheng. When Division II command center was seized by the enemy, Gen.Vang Pao decided to go and meet with Prince Souvanna Phouma at his residence in Vientiane. As soon as he showed up, the prince yelled at him, “Vang Pao, you really like fighting war?” Gen. Vang Pao answered, “I would like to return my general’s hat and my stars to you; I’m asking you to accept my resignation.” He pulled his hat from his head, his two stars from his epaulettes, and put them down on the table in front of the Prime Minister, and then walked away to get on board his car and drive to the Wattai Airport en route to Long Cheng.

This incident happened on March 9, 1975. It was reported later that Prince Souvanna Phouma sent an aide to try to get Gen. Vang Pao back to meet with him, but it was too late. On March 12, 1975 Gen. Vang Pao flew to Louang Prabang for an audience with King Savang Vatthana in his palace, seeking his advice out of concern for the country and its population. Gen. Vang Pao said, “I’m here to seek an audience with your Majesty and find out what you would order me to do to address the serious situation we are facing.” The king answered, “I do not need anything else; I only need this house to live in and this piece of land to grow rice!” Gen. Vang Pao and I (who accompanied him on this trip) clearly heard his statement. I patted the back of Gen. Vang Pao to suggest no further conversation—just leave and go back to Long Cheng.

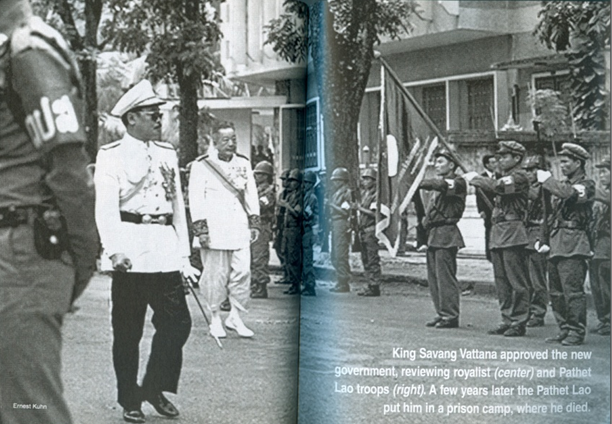

On second thought, it could be seen that people all over the country, including police, military and civilian authorities of all ranks, the public at large and even His Majesty the king, did not fully understand the communist doctrine and how bad it really was. It was reported that in 1973 the Lao communists had invited His Majesty the king and several Vientiane leaders to pay a visit to the Vieng Xay Lao communist command center, and welcomed them with great honors. King Sisavang Vatthana even went on to admit that the Lao communists respected him more than the Vientiane faction.

Furthermore, it appeared that many Vientiane leaders very surprisingly also believed the same way in the Lao communist game play, and refused to recognize that communism was against royal dynasties, and was after leaders, capitalists, religious and political parties. As far as the communists were concerned, the only thing that counted was their central committee which detained all decisive power. Only when people had a chance to observe communist practices did they get a good flavor of what those practices really meant. By that time, it was too late to fix anything. Students and national employees organized public demonstrations against the rightist leaders –their own elders—and forced them to flee the country as political refugees. In the end, many of those short-sighted individuals also had to run behind the old leaders and their family elders, seeking refugee status in foreign countries. Gen. Bounpone Mart-Thepharat, Royal Lao Army Commander-in-Chief, was also lured into believing in the communist doctrine. After leading his staff into attending informational meetings at the Chinamo Camp, he and 46 thousand of his soldiers ended up in communist re-education camps. Gen. Bounpone and members of the royal family were also lured into going to the Vieng Xay re-education center, Houaphan Province where they died.

Photo #142. H.M. King Savang Vatthana on his visit to the communist town of Vieng Xay in 1973

Photo #142. H.M. King Savang Vatthana on his visit to the communist town of Vieng Xay in 1973

Photo #143.North-Vietnamese attacked and wiped out Division II headquarters at Sala Phoukhoun in March 1975.

“Please read the book on the Vientiane leaders’ fates at the Vieng Xay Camp, Houaphan Province and see for yourselves how much suffering was involved. You should read the book, “Get to the Trunk, Destroy the Roots –The Fall from Monarchy to Socialism”, written by former Col. Khamphan Thammakhanti. His wife, daughter and son-in-law can still make that book available to readers across the world. Col. Khamphan’s daughter, Nang Chanh Vannarath, can be contacted at 7321 SE 20th Ave., Portland, OR 97202-6211″. Col. Khamphan was released from the Vieng Xay prison and came to the USA in 1990. He passed away at the age of 74 in Portland, OR on August 26, 2004. (Thank you, Christopher Kremmer, for telling us about the book).