In 1981, a Front for the Liberation of Laos was created under the leaderships of the following personalities: Inpeng Souryadhay, Tiao Sisouk NaChampasak, Ngone Sananikone, Khamphanh Panya, Kouprasith Abhay, Houmphanh Sayasith, Phoumi Nosavan, Vang Pao, and Chao Phaya Luang Outhong Souvanavong (President). In 1982, Tiao Sisouk NaChampasak died of a heart attack in California. , and Gen. Phoumi Nosavan died in Thailand of old age.

The Liberation Front sent many letters to the US Government and the United Nations asking them to help address the invasion of Laos by North-Vietnam, who killed innocent Lao people, and treated Laos as a colony. This action produced no results, because the foreign newsmen who went for site reporting in Laos were lied to and misled by the Lao communists, the North-Vietnamese’s protégés. Those foreign reporters who came to collect information were only allowed to urban areas, not to rural or remote areas for security reasons. But in 2004, members of the Fact Finding Commission (FFC) were able to go to Laos and share the pictures they took with the rest of the world. Still, they could not do anything to control and/or punish communist North-Vietnam.

On December 10, 1989 Gen. Vang Pao announced the formation of a “Revolutionary Lao Government” in exile with the purpose of securing freedom for the people of Laos, especially the Hmong, but some US politicians framed the Hmong as terrorists. Gen. Vang Pao was arrested on June 4, 2007 and released on December 7, 2007, but his case was still pending. The case was reopened on May11, 2009, without any results. The hearing was rescheduled for October 5, 2009 when the case was dismissed for Gen. Vang Pao, with eleven other Hmong still waiting for their cases to be heard. [Nine Hmong were arrested at the same time as Gen. Vang Pao, and two others were arrested later]. The false incrimination and the lengthy court hearing took a toll on Gen. Vang Pao’s health conditions.

This was an unfortunate instance where the US appeared to have opened the door to the communists to come in and created misunderstanding among US citizens. Two more important facts seemed to have been underestimated. First, people tend to forget that Laos had signed itself off to North-Vietnam’s colonization for twenty-five years from 1977 to 2002, a contract that can be extended every ten years with no expiration date. Second, the killing of Hmong in Laos and the detention of 46,000 high-ranking military officers and civil servants in re-education camps still has yet to be addressed.

Summary of Hostilities-Related Human Losses

- 1945-1947: the Lao Issara rallied its supporters against the French to get rid of colonization. There were more than 10,000 deaths among the Lao, French and Vietnamese ranks, mostly in southern Laos and in the provinces of Vientiane, Xieng Khouang, Luang Prabang and Houa Phanh.

- 1953-1954: the war between the French and the Vietminh caused the loss of about 30,000 Lao citizens, mostly in the provinces of Phongsaly, Houaphanh, Xieng Khouang, Savannakhet, and Pakse. These were the sites of fierce battles with the Vietminh that were pushed away by the French guerillas.

- 1960: the Kong Lae’s coup d’état in Vientiane caused several hundreds of military and civilian deaths in the capital city of Vientiane and in Xieng Khouang Province. That same year, when Gen. Phoumi Nosavan and his troops reoccupied Vientiane, almost one thousand Lao military and civilians died.

The fight against communist expansion into southeast-Asia caused the following losses:

- Military Region I (MR-I)

About 20,000 civilians and 25,000 military were killed, in addition to the loss of 70 percent of the territory to the North-Vietnamese enemy in the northern and eastern parts of MR-I, and the entire Phongsaly Province. Over 60 percent of the population of MR-I (Oudomsay, Louang Namtha, Louang Prabang and Sayabouri) was pro-communist because they did not have any other choice and had to lean to the left to survive.

- Military Region II (MR-II)

About 100,000 civilians were arrested, tortured and killed by the enemy, or died from air bombing; and about 50,000 military (70 percent highland Lao Hmong and 30 percent lowland Lao) were killed in the action. Several thousands of Thai troopers were also killed. Sixty percent of the territory was lost to the enemy. In 1967, a radar station was set up in Houaphan Province to guide air raids over Hanoi. Therefore, this province became the target of heavy attacks by North-Vietnam. Of all the Laos provinces, Xieng Khouang Province shared the longest borderline with North-Vietnam and was located the nearest to Hanoi. In addition, Houaphan and Xieng Khouang Provinces served as hiding and training sites for the North-Vietnamese troops, as command centers for the Lao communists, and as the defensive front line for the capital city of Vientiane and the royal city of Louang Prabang. For all these reasons, those two provinces were more heavily attacked by the North-Vietnamese than any other MR’s.

Safely Running Away From Bouam Long (LS32)

In 1976, one soldier left his family behind and fled across the mountain ranges into Thailand. When he later met his friends and bosses, he said that as soon as his commanders fled abroad he and his colleagues almost fainted, ran out of breath, and did not know what to do. Some dropped on their knees, started invoking the holy spirits, and put their hands on the ground desperately praying for divine advice. When Col. Cherpao Moua, commander of the Bouam Long, was informed of the situation, he decided to go back to Laos to see whether he should bring his troops out of the country or continue fighting. They took a vow to do everything together –leave together or die together. They fought together because they did not like the communist regime that lied to people and used them. Col. Cherpao went back and fought until 1994, and died in the jungle of Laos.

After the war and still today, the communist party has engaged a genocide against the Hmong still resisting in the jungle.

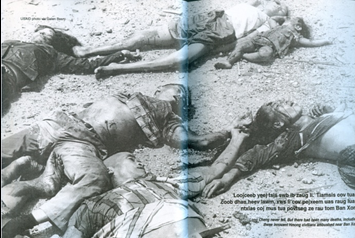

Photo #211. Female teen-agers were raped and killed like animals by the communists in 2004. (These pictures were taken by Fact Finding Commission from France and made available on the Internet.)

Photo #211. Female teen-agers were raped and killed like animals by the communists in 2004. (These pictures were taken by Fact Finding Commission from France and made available on the Internet.)

Photo #212. Bodies of Hmong killed at the bridge over the Nam Lik River in May 1975. About 50 bodies were buried at Ban Na Sou by a USAID team led by Tong Voua Mua (who later died in South Carlina on March 14, 2010).

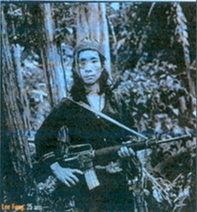

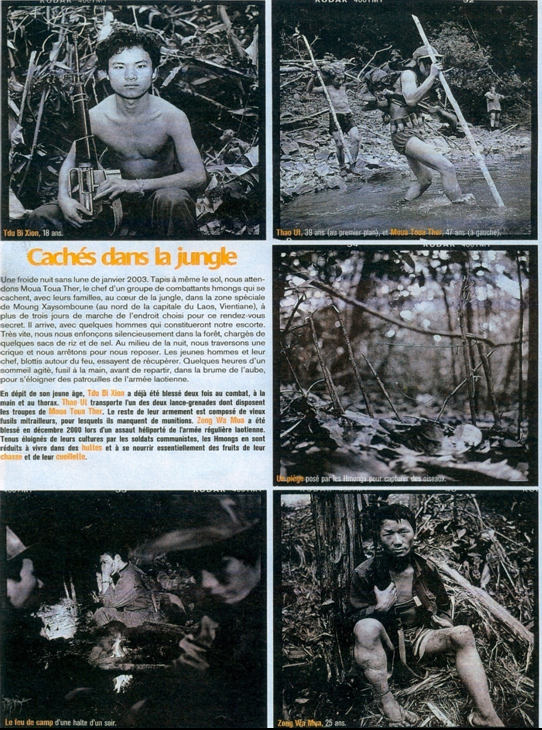

Photos #213 (left) and 214 (right). Hmong soldiers had to continue fighting in the jungle on a day to day basis in order to survive, avoid surrendering and/or cooperating with the communists, and being captured and killed like animals. Photo courtesy Fact Finding Commission, 2004.

Photo #215. Fighting for survival, always on the move, and setting up traps. No matter how difficult and painful, one had to fight and die with honor to avoid being caught and savagely executed like animals by the enemy. Sleep where and when you can.

Photo #215. Fighting for survival, always on the move, and setting up traps. No matter how difficult and painful, one had to fight and die with honor to avoid being caught and savagely executed like animals by the enemy. Sleep where and when you can.

- Military Region III (MR-III)

More than 100,000 civilians were killed by the enemy, arrested and tortured to death, or died from air-bombing –the heaviest casualties anywhere in the world since the Second World War. Military losses were over 50,000 in the provinces of Kham-Mouan, Savannakhet, and Saravan (which was totally occupied by the enemy since 1965 for use as part of the Ho Chi Minh trail). About 70 percent of the MR-III territory was lost to the enemy.

- Military Region IV (MR-IV)

More than 60,000 Lao civilians and about 30,000 military were killed in MR-IV, an area used by the North-Vietnamese to hide their armed forces and send them to South-Vietnam. The communists had to cleanse all the Lao civilians from MR-IV to keep them away from military centers of the North-Vietnamese and their Viet-Cong allies. MR-IV had to fight very hard to protect itself and, in the process, suffered formidable losses, especially in the high Boleven plateau and several eastern locations. It lost all its territory along the border with South-Vietnam and Cambodia, and had at times to ask for support from the Thai Army. About 60 percent of its territory was occupied by the enemy. The provinces of Sedone and Attopeu fell entirely in enemy hands in 1965.

- Military Region V (MR-V)

This military region suffered the most chaotic situation of all MR’s because of the influence of the internal and external political changes that took place. It was the site of many foreign embassies and the center of the Lao coalition government –not the site of too many armed conflicts but definitely the site of fierce political fighting. Because of the presence of the foreign embassies, the split between the three Lao factions was not too obvious, despite the fact that the leftists and neutralists used every possible tactic to eliminate the rightists. When the rightists were gone, the only faction left was the communist faction. This gave Kaysone Phomvihane, Secretary-General of the Lao Communist Party and member of the Indochina Communist Party since 1944, the opportunity to put Laos indefinitely under the control of the North-Vietnamese communists for 25 years followed by renewable 10-year terms. This was supposed to be a mere Laos-Vietnam Friendship Treaty, a treaty that actually left Laos with no power and no Army because the North-Vietnamese are now in charge of the country’s defense. MR-V suffered no or very little, if any, civilian or military losses during the early stages of the fight against the communist armed forces. But once the Laos Communist Party took over power, MR-V was the MR that recorded the most civilian and military losses, based on the 40,000 rightists and neutralists who died at the Vieng Xay re-education camp. MR-V was full of civil servants, and an MR where the highest number of refugees originated from.

Population Movements

The power take-over by the Laos Communist Party in 1975 forced more than 600,000 Hmong that lived in northern Lao provinces to move as follows:

- About 200,000 remained under the direct control of the Lao Communist Party, as some of the Hmong did fight alongside the Lao and North-Vietnamese communists between 1945 and 1975

- More than 30,000 went into hiding in the forest to engage in guerilla fighting. For them, collaborating with the Laos PDR would not be safe, because they had been fighting them for a long time (from 1960 to 1975). As of 2010, only about 2,000 of those guerillas were still alive.

- About 100,000 tried to immigrate to Thailand, but never made it there. Some died of hunger, thirst, gun shots, armed robberies, exposure to yellow agent rain, drowning during Mekong River crossing, boat sinking, malaria, etc.

- About 200,000 survived and reached the Thai Mekong River bank and then went on to start a new life in a third country. Over 140,000 went to the USA, over 60,000 to France, French Guiana, Canada, Australia, England, and other countries. In 2008, several Hmong were still in Thailand, but in 2009 they were sent back to Laos PDR.

- Currently, there must be at least 400,000 in the USA, including the states of California, Minnesota, Wisconsin, North-Carolina, South-Carolina, Georgia, and other states. Most of the Hmong who had resettled in those states have had good opportunities to get an education, and become economically self-sufficient. This was a big improvement compared to when they first arrived and needed interpreters, social welfare, road guides, etc. because they did not understand and could not read English.

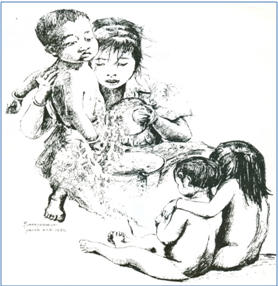

Photo #216. The war torn family system leaves only women behind to care for children. This picture was drawn by Ms. Halinka Luangpraseut, Khamchong Luangpraseuth’s wife (who now lives in California, USA).

Photo #216. The war torn family system leaves only women behind to care for children. This picture was drawn by Ms. Halinka Luangpraseut, Khamchong Luangpraseuth’s wife (who now lives in California, USA).

As for the lowland Lao, at least 600,000 of them, especially high-ranking military, police, and civilian personnel and their families, have resettled in several foreign countries. Almost 100,000 of them went to France and other European countries. Over 300,000 of lowland Lao, especially those who went to school in the USA or have fought in the US rank in the Indochina War, came to the USA with their families and started a new life mostly in the following states: Texas, California, Georgia, North-Carolina and South-Carolina. Since most of them were educated people, they faced less of a challenge in the new environment than the other Lao ethic groups. Finally, no less than 100,000 Lao refugees ended up in other countries like Canada, Australia, Thailand, Japan and the Middle East.

All told, it appeared that the lowland Lao refugees who resettled in the USA are better off than those who went to other foreign countries. Many of their children and grand-children were able to get higher education, and almost all the families are at fairly decent standard of living at the Lao society scale. By comparison, the highland Hmongs, on the other hand, are in a tighter situation. Most of them were not well-educated, having spent most of their lives fighting a lengthy war and not getting too many opportunities to develop themselves. This is why many Americans treated them as “stone age” people. In 2010, many of the Lao refugees who came to the USA have been in this country for a full 34 year period and appeared to have done reasonably well. Many have become specialists in several professional fields and have adapted themselves to a new live in a new country.

Short Stories About Early Hmong and Lao Refugees in the USA

1. A lowland Lao man, who drove his car past the traffic lights, got arrested by the police. He was asked, “Can’t you see? Why did you run through the red light?” The man answered, “No money, no country, thinking, thinking, no see!” The police officer then asked for his address, told him to get on the police car, and drove him back to his apartment. The police officer went inside, looked at the refrigerator and the bedroom. He saw only two bottles of milk and some ice cubes in the refrigerator. He told the man to come with him to the Social Service office. When they got to the office, he asked the Social Service official to give the man several hundred dollars worth of food stamps. He then took the man to a grocery store, bought tens of food items, and brought the man back to his apartment to unload the grocery in the refrigerator. The man later confessed that when he got on the police car, he was scared to death because he was afraid he would be put into jail and forced to pay a fine. He had no money to pay for anything. In the end, he bowed to and saluted the devout police officer who was so compassionate toward a poor refugee. The man told his story with joy and tears flooding his cheeks. He now lives in Minnesota.

2. In 1976, a Hmong family was sponsored by a group of Christians to start a new life in the USA, doing farming and cattle breeding. The sponsors needed assistance in that field and believed, through some research, that the Hmong family would do just great in that type of activity. The Hmong family arrived in Iowa in February of that year, a frigid month for that state. They were greeted warmly and put in a house located about a mile from downtown, near a cornfield owned by local American farmers. The church’s pastor took them inside the furnished house, put the light switch on to bring heat, and loaded the refrigerator with food. After handing the house keys to the family, he then left. This was on a Friday evening.

That Hmong family did not know how to light the fire-place, open the water faucets, cook food, or even open the fridge. All they could do was to sit around and wait for somebody (maybe an interpreter) to show up for a visit. The whole family waited and waited, with nothing to eat, from Friday evening to Sunday evening, when the wife of the pastor was the first person to drop by. She saw the family members all clustered together to stay warm, hungry and cold. When she opened the fridge and noticed that everything in there was left untouched, she realized the family did not know what to do at all. She then called for an interpreter from the Refugee Center.

The interpreter, a lowland Lao native, came and took care of everything. He then joked with the head of the Hmong family, “You are too stupid. This evening, I’m going to take your wife away.” The highland Lao man was a very jealous person, and thought this was going to really happen. If it did, he wouldn’t know what to do; he had no relatives nearby and couldn’t even speak the language. So, in the evening, when the visitors were gone, he told his wife to hang a rope on the basement’s ceiling, brought in a table, and had everybody –husband, wife and their three kids—climb on the table and lay their feet on it. He tied everybody’s neck with the rope, beginning with his wife and moving on to the children. When he was tying the neck of his children, his wife quickly removed the rope from her neck and hid the rope in her hands. The husband tied his own neck and then kicked the table away to hang himself. The wife was able to untie the rope from the neck of one of her children and her husband. But she could not help her other two children before they were choked to death. The husband’s neck was twisted badly, with the husband himself being unconscious. The wife ran out the door crying, and continued running barefoot on the snow toward the nearest neighbors’ house to call for help. When the neighbors arrived, they could not save the life of two of the children. They were able to save the husband’s life, and took him to the hospital. Ever since, he became physically weak and emotionally unstable.

The Christian sponsors later moved this Hmong family into town, closer to the other Hmong refugee families to allow for more social connections. They also discontinued their sponsorships of the Hmong families. [The Hmong family referred to above came from the Soune Phayao refugee camp in northern Thailand designed to provide shelter to refugees from Sayabouri Province]. Their main objective was to save Christian Hmongs, allow them to restart a new life and get to know Christ. This particular Hmong family came to the USA without much further thought and, besides, has not yet accepted Christ. Since their friends have left, they just wanted to follow them in order to stay away from the refugee camp uncertainty.

3. In 1979, the US Government provided funds to accept refugees who were members of the Vientiane faction’s civil service, military and police, and used to fight the Indochina war against North-Vietnamese communists alongside the US. Those funds were limited to refugees from the Ban Vinay Refugee Camp, Thailand –not from any other refugee camps— and designed to cover bus expenses. But when the buses arrived at the Ban Vinay Camp, many refugees changed their mind about coming to the USA, thus leaving some room to accommodate refugees from other Northern Thailand camps such as Soune Phayao, Soune Nan, etc. Those refugees were not educated and used to live in rural areas, away from the cities and modern conveniences. The Lao Communists had plenty of time to lure, coerce and isolate them from the Vientiane faction’s influence. Very few of them fought the communists in the ranks of the Vientiane faction. For all these reasons, the highland Lao Hmong had a lot of problems getting adjusted to a new life. Hence, the US policy to only accept refugees who used to be civil servants and police and military officers that fought the Indochina war with the US, especially those who immigrated to Thailand during 1975-1982. Despite that policy, the US was still accepting refugees until 2006, with those from the Tham Kabork Camp being the last batch of refugees admitted to the USA.

4. Reports on actions taken by the Lao PDR against the Vientiane faction and the cleansing of the highland Hmong who took refuge in the jungle were based on testimonies made by several people who were personally involved in the brutal actions committed by the Lao PDR at the re-education camps of Vieng Xay, Houaphan Province and many other locations. The decade-long incidents deserve to be recorded as lessons learned for the younger generation, because Laos is the middle of several countries who are interested in investing in our country. We have to recognize that Laos is sparsely populated, hard to protect, not fully secure, constantly faced with invasive border problems, and had been embroiled in a long and almost endless internal fighting. The last war might have ended, but another one may break out again in the future, as it is evident that the competition among our neighboring countries may not die down anytime soon. Everybody wants to start investing in Laos, but once they have done so, would refuse to leave, claiming they are Lao citizen because it is so easy to forge an identity in Laos.

Photo #217. Col. Bill Lair and Gen. Vang Pao met in Saint-Paul, MN in 2008 to form the SGU Veteran Association in the United States

Photo #217. Col. Bill Lair and Gen. Vang Pao met in Saint-Paul, MN in 2008 to form the SGU Veteran Association in the United States

My Dreams

I have a dream that my country finaly finds peace for a long time. This is what Laos deserves after so many years of suffering in foreign wars.

This dream can come true when the following conditions are met :

– A close collaboration between this generation of laotians : those who live in the country and those who could study abroad while building foreign know how. We should expect mixed blood laotians to strenghten networking with neighbouring countries. This would allow friendly relationships with all South East Asia and stimulate peace in the area.

– A neutral political position with regards to world super powers. Laos and other small countries in South East Asia absolutely need to keep a balance when relying on both USA and China Republic so solve political and economic issues. If not, peace and independance are jeopardized.

The world moves at a fast pace in all aspects : economy, population, politics, etc. Our future is not written down in stone. There are great hopes but also great fears that Laos would miss the opportunity to get on the fast track. However, I believe Laos is ready to face this challenge as its population has well mingled and is better educated than in the past. War has massively displaced laotians to rich countries with better opportunities. Next laotian nation will have higher chances to succeed when they learn how to benefit from these riches.

We have suffered more than enough during the Vietnam War. It is time for peace and economic prosperity for the people of Indochina.