2.1 The French Entered Laos

The French officially entered Laos on November 10, 1861. In 1872, hordes of Chinese red flag, yellow flag and multicolor flag troops invaded the northern part of Laos. The French leaders contacted the Hmong and recruited them to fight against the invaders. The successful operation increased French confidence in the Hmong. In May 1893, the French used their armed forces to remove Laos from Siam’s control and put Laos under their own control as a French colony. They first named Chong Kai Moua as the first “Kaitong” (subdistrict chief) of the Hmong subdistrict of Nonghet, and then Lor Blia Yao (1913-1934). As administrators of Laos, the French next selected Touby LYFOUNG to be the Nonghet subdistrict chief until 1945, during their war against Germany and Japan, and right before their war against North-Vietnam. After losing those two wars, the French were forced to move out of the Indochina peninsula per the Geneva Treaty.

2.2 Toulia Lyfoung’s Memoirs

On March 15, 1994 Toulia Lyfoung published his memoirs on the history of the Lao Hmong to remind the new generation about the past. Many parts of those memoirs are reproduced in the following sections. Throughout the Laos history, the Lao Hmong have always been part of the country administrative, military and police structure, especially when Laos was a French colony. During 1945-1954, the Lao Hmong have been fighting alongside the French in the Indochina war against the Vietminh and the Lao Issara.

During 1959-1973, the Lao Hmong collaborated with the Royal Lao Army and the US armed forces in the fight against the communists along the Northern Laos border. During the fight near the borders of the Soviet Union and Communist China, the former delivered tons of war material to North-Vietnam in 1970. From that point on, the US felt compelled to change their overall strategy in Indochina.

2.3 The Lao Hmong

The Hmong Emigrated from China to Laos

Around the year 1750, Hmong emigrated from China and settled around the highland mountains of Laos along border areas that were covered by forests and far removed from urban centers normally occupied by lowland Lao and other tribes that have resettled there before. They feared persecution from the Chinese. They also feared discrimination and violence from the Lao ethnic majority because they did not yet speak Lao, and were not familiar with Lao leaders and Lao customs. The Hmong feared ghosts in the cities of Laos because many became sick and died after they returned home from venturing into town. In the mountains the weather is cold, so mosquitoes rarely caused malaria. In the lowlands, however, the weather is warmer and contact with mosquitoes and ticks does cause deadly cases of malaria.

For all those reasons, only few Hmong were able to live in the cities. Most of them would stay in the mountain areas away from cities, which prevented them from receiving an education and getting to learn Lao and French. During those times, the Lao who lived in the cities were more educated, could speak French, and often acted as representatives of the French Colonial Administration in making surveying contacts with the Hmong living in the mountains and the various villages. The French then set up taxation codes that created a lot of problems for the Hmong and eventually caused an armed resistance from them. The revolt was led by a Hmong leader named Paj Caiv Vwj at the village Pak Kha in between Houaphan Province and Xieng Khouang Province. The French dispatched Vietnamese soldiers to control the revolt in a very ferocious and barbarous way during 1919-1922. Paj Caiv surrendered to the French in 1922.

During the French persecution of the Hmong, the Lao leadership had little say in the conflict and in fact had to side along with the French because they were under the French control and because the Hmong had refused to pay the implemented tax. The Hmong did not have any fire-arms to fight against the French except for guns used for hunting; they relied only on Chao Fa’s spiritual power for their protection and fought as isolated groups, with the rest of their family members. For this reason, many people referred to this revolt as “Crazy War.”

Tou Lia Lyfoung noted that anyone over eighteen years old must pay seventy-five brass coins in tax per year, but the Lao Leadership, who did the tax collection, did not exactly follow the tax code. They instead collected twelve more brass coins, for a total of eighty-seven brass coins. At the time, mostly the Hmong were poor people, had no income, and could not afford to pay the tax. To avoid jail detention, some Hmong had to sell their children to pay tax, which caused uprising among most people. The French did not listen to the motives, sent in military forces to barbarously persecute the Hmong and caused many fatalities. Those who did not get killed were incarcerated and many of them were later sent to the firing squad.

This news spread to the Hmong in China, who threatened to send Chinese Hmong to help the Lao Hmong in Laos. Later on, Father Savina (a French preacher) came to intervene to stop the French from persecuting the Hmong. He was able to save the life of about 100 people who were already handcuffed and waiting in line for public execution at the sports stadium of Xieng Khouang. Father Savina also called for no more arrests and no more executions of the Hmong by the French. After that, the fight for justice led by Paj Caiv ended.

Not long afterwards, during that same year 1922, Soob Ntxawm Lauj, a Hmong from Nonghet, led another fight for justice. This time, the French have just completed the construction of Highway #7 from Ban Ban to Nonghet, and from Nonghet to Muang Saene in Central Vietnam. They gave Kaitong Lor Blia Yao the authority to recruit laborers for the road construction, and set the labor rate at 20 brass coins for the excavation of a one square meter hole, regardless of its depth. Even though the excavation had to be deeper than before, the daily labor rate still remained the same. When the project owner acted unfairly, the laborers stood up. Many people started screaming, “The crazy war is back!”

[Soob Ntxawm Lauj had a nephew named Soob Thaiv Lo, who is a refugee living in North-Carolina. During 1960-1970, Soob Thaiv Lo served as a member of the US-FAG in the Vietnam War. He flew backseat with the US pilot of the small airplane that flew in to locate enemy positions, reported that information to the US ground forces, and sent for air strikes. Soob Thaiv Lo was shot by enemy’s anti-aircraft during one of his flights. He was wounded in the head, but luckily the pilot was able to bring him back to the airfield and transported him to the U.S. hospital in Thailand. He survived from the good treatment at the US hospital and is now well-known among the Hmong people].

After the Crazy War the French changed their policy to the Hmong by using Hmong to lead and controlled Hmong people.

Tou Lia recorded that the French named Kaitong Lauj Blia Yao as a leader at the Kaitong’s level during 1913-1934 to replace Chong Kai Mua. After Lauj Blia Yao died, his son Chong Tou Lauj took his place as leader of the Hmong. During his term, several incidents took place within the Lee family. After Chong Tou Lauj died, his son Hnia Her Lauj replaced him as leader. After Hnia Her died, two brothers (Hnia Veu Lee and Ya Lauj Lee) and descendants of the Seng Lee family joined force with the French to fight the Ho (Chinese) burglars who invaded and pilfered northern Laos in 1872, building themselves a good reputation within the Hmong and the French communities, and enhanced the French’s confidence in the Hmong. (Kaitong was a leadership position during the Annam’s administration, similar to the position of Tasseng under the Lao administration). After the Seng Lee brothers, Ly Foung was named the next Hmong leader.

During the terms of Kaitong Blia Yao Lauj, Ly Foung served as his assistant and was his son-in-law. Ly Foung did great things for the Lee and other Hmong families. He was a smart man, and could read and write Lao pretty well. However, his wife (the daughter of Kaitong Lauj) poisoned herself to death. Her father became very disturbed and had Ly Found put in jail in Xieng Khouang for several months. These events forced Ly Foung, who did not know how to speak or write French, to send his four sons (Nao Chao, Touby, Tou Lia and Tou Geu) to school in Xieng Khouang. Kaitong Lauj did the same by sending Lauj Foung to school, where he later graduated as a teacher. As for Nao Chao, he was not able to complete any schooling and came home empty-handed.

Tou Lia graduated third of his class from a law school in 1941. While at school, he felt in love with Tiao Khampheng, a member of the Louang Prabang front royal lineage. The two got married and has three children together, all of them boys. Because of his good education, Tou Lia was assigned to work as a staff member of the Royal Office in Louang Prabang during 1941-1945.

Photo #1. Kaitong Lo Bliayao, first Hmong Leader In Nong Het, Xieng Khouang

Photo #1. Kaitong Lo Bliayao, first Hmong Leader In Nong Het, Xieng Khouang

Photo # 2. Typical dress of a Hmong woman before 1920

Photo # 2. Typical dress of a Hmong woman before 1920

The Hmong People Fought the Lao Issara and Viet-Minh Alongside The French

In 1946, Tou Lia returned to Xieng Khouang to join hands with Touby Lyfoung in leading the Hmong people to fight, alongside with the French, the Lao Issara and the Vietminh invaders. In 1947, Tou Lia was elected as Xieng Khouang’s state representative and went to work in Vientiane until 1954, when he came back to Xieng Khouang for a break. In one of his personal records, Tou Lia noted that in 1941, he walked from Nonghet to Xieng Khouang, about 100 km, to meet with David Beaulieu, the French Commissaire (Administrator) of Xieng Khouang Province. The Commissaire invited Tou Lia to have breakfast with him at his official residence and asked him, “I’ve heard that you came to push the Hmong people against the French. Is that true?”

Tou Lia answered, “Where did you get this information?” and added, “I’m ready to face your informant.” The French Commissaire did not answer the question but added another one, “What brought you down here in Xieng Khouang?” Tou Lia answered, “I am here to ask you for an official note to visit Hmong relatives at the border of Vietnam and Laos.” After that, the Commissaire told Tou Lia, “Tomorrow, please come and meet with me in my office at 9:00 a.m.”

Tou Lia wrote that when he entered Mr. Beaulieu’s office as invited, many people were already sitting in the room, ready for a meeting. During this meeting, several personnel changes were made, involving some transfers and some dismissal as follows:

- Phoumi Vongvichit, the Chaomuang (District Chief) of Xieng Khouang, was moved to become the Chaomuang of Vientiane;

- Bouasy, the Xieng Khouang’s legal officer, was reassigned as the assistant of the Chaomuang of Savannakhet (Southern Laos); and

- Thao Cham, the Muang Kham’s legal officer, was discharged from his position because he was accused of being too self-centered in his duties performance. He was sent to early retirement in Savannakhet.

Tou Lia also wrote some notes about the Second World War and the Indochina War. During the Second World War, when Germany and Italy invaded several European countries, especially France that was heavily assaulted, towns and cities were badly damaged and people fled everywhere. France almost did not survive. In Asia, Japan stood up to fight against the western powers and had its own plan to take power in Asia. Japan lost the war and left behind weapons in several Asian countries to help those countries in their fight to regain independence from their western conquerors.

During 1939-1954, the three countries in French Indochina (Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam) fought against the French colonization. During this fight, French troops under the command of General de Lattre de Tassigny asked for US assistance and set up a defense stronghold at Dien-Bien-Phu in order to teach the Communists a lesson. Due to the lack of stronger US interest, France lost that war. The US has also agreed with Ho-Chi-Minh to hold a conference in Geneva, Switzerland on May 21, 1954. The Communists and Ho-Ch-Minh needed a military victory before the scheduled conference and fought hard to defeat Dien-Bien-Phu on May 7, 1954. France thus lost the war and had to sign an agreement to grant independence to the three Indochina countries on July 20, 1954 (instead of May 21, 1954). For that very reason, the US did not sign the agreement–only 13 countries did.

During 1945-1954, the Hmong fought with the French. Even after the French pulled out of Indochina, the Hmong continued to fight relentlessly against the Vietminh. They disliked North-Vietnam’s despotic regime and felt they had to protect their homeland in the mountains from being used as a hiding place or a military base for the North-Vietnamese troops. They knew the North-Vietnamese would just not let anybody who fought them alongside the French to continue to live in those areas.

Tou Lia went on to write the biography of Captain Bichelot (the local French leader), Chao Saykham, and Phagna Touby Lyfoung. These three leaders joined forces and led the fight against the Lao Issara and Vietminh in the liberation of Xieng Khouang, from the morning of January 25, 1946 until the evening of January 26, 1946. They initially ordered a retreat on the evening of January 26, 1946 based on lack of food supplies and the fact that the Hmong, who took part in the operation, only had outdated guns that could not fire bullets very far. Immediately thereafter, Say Pao Vang, the leader of some 300 Hmong troops from Muang Pha and Na Vang, told argued against the retreat order, “If we pull out, reoccupying the high positions around Xieng Khouang later would not be easy. We need to continue one more day and see what happens.”

One day later, on January 27, 1946, the calmness of the situation around Xieng Khouang prompted Captain Bichelot to send in a scouting team. The team found that the Vietminh and the Lao Issara had already left the area, leaving no one behind. The liberating troops then moved in the central part of the town of Xieng Khouang, and later used it as the command center of the French, Lao and Hmong troops.

Say Pao said that from that point on, each time he made any suggestion, Touby always listened to him. At the battle to liberate King Sisavang Vong in Louang Prabang in 1946, the leaders of the anti-Lao Issara troops had Say Pao Vang dressed up as the king during a procession through town to announce that the (real) king had been freed. This make-up was for security reason, and did not prevent the by-standers to pay respect to the (fake) king.

[Say Pao had been the only surviving member of the Xieng Khouang liberators for a long time. He was born on May 5, 1919 in Xieng Khouang, Laos and passed away on May 15, 2011 in Georgia, USA].

Touby LYFOUNG Liberated Xieng Khouang for the French

In February 1945, Issara leader Prince Phetsarath appointed Phoumi Vongvichit, a high-ranking Chao Muang Grade 5 official, to replace Thao Lek Sengsathith as the Governor of Houaphan Province. Thao Lek was Phoumi Vongvichit’s father-in-law, and had been bestowed with the royal honorific title of Phagna Muang Khoua. Prince Phetsarath also instructed Thao Lek to liberate Xieng Khouang from the French and to serve as Governor of that province. Thao Lek and Colonel Sing Rattana Samay, a Lao Issara military officer, led a contingent of North-Vietnamese and Lao Issara troops in seizing Xieng Khouang on November 28, 1945. As mentioned earlier, less than two months later, Governor Chao Saykham and Phagna Touby Lyfoung led Hmong troops in the reoccupation of Xieng Khouang. This action angered the Lao Issara leadership –Tiao Phetsarath, Tiao Souvanna Phoumma, and Tiao Souphanouvong. After liberating Xieng Khouang, the pro-French troops arrested Phagna Muang Khoua and executed him at the Sanam Luang stadium in Xieng Khouang. It also pushed Phoumi Vongvichit to join the Vietminh and fight against the French and the Royal Lao Government.

During the Second World War, Japanese troops invaded Laos on March 9, 1945. Japan, the Lao Issara and the Vietminh mobilized troops to fight against the French to recover their independence. For his collaboration with the French, Touby Lyfoung was promoted to the rank of Nai Kong (district chief) of 4th class on August 28, 1946, to the rank of Oupahat of 1st class in July 1947, and to the rank of Chaomuang of 4th class soon afterwards. Lao and Hmong leaders who fought with the French against the Lao Issara in Houaphan and Xieng Khouang Provinces in 1946 included Touby Lyfoung, Chong Toua Moua, and Chao Saykham Southaka Koumane.

On November 1, 1949 Touby Lyfoung was promoted to the position of deputy-Governor in charge of Hmong affairs within Xieng Khouang Province, and was conferred the honorific title of Phaya Damronglithikay (“the trusted guardian of high power and authority”) by H.M. the King of Laos. Later on, he also got several high-level medals and decorations from the French and the Lao authorities.

Photo #3. Mr. Lyfoung and his family in 1928 at Nong Het, Xieng Khouang, Laos. Mr. Lyfoung was born in 1888 and died on December 12, 1939. He was the son of Mr. Lypao (Ly Dang Pao). Front row, left to right: 1. Touby (3rd son); 2. Tougeu (4th son); 3. Toulia (5th son); 4. Mr. Lyfoung (head of the family), 5. Nang Mao No (daughter, who later was married to Mr. Tou Ly, Gen. Vang Pao’s older brother. After Tou Ly died in a car accident, she remarried with Col. Mua Su, son of Col. Cher Pao Mua. Nang Mao No died in Georgia, USA in 2006.); 6. Kue Choua Lyfoung (Mr. Lyfoung’s 3rd wife, carrying her son Chou, died in 1929); 7. Mr. Lyfoung’s daughter Mao Song (she later became Mrs. Vang Nkaj Zeb. She was the mother of Col. Vang Neng, from France. She passed away in 2006 in the US). Second row, left to right: 1. Ly Chao (first son of Mr. Lyfoung); 2. Yang Tongxeng (brother-in-law, married to Phauj Zuag); 3. Ly Pobzeb (2nd son of Mr. Lyfoung, served as Tasseng, later died falling off a horse saddle; his wife then became his brother Touby’s second wife); 4. Thoj Blia (wife of Mr. Ly Chao); 5. Mrs. Lyfoung, born Yang Va (Mr. Lyfoung’s first wife, died in 1945); 6. Mrs. Tongxeng Yang, nee Mao or Paj Zouag. This picture was taken by Prince Phetsarath during his visit to Xieng Khouang during 1927-1928.

Photo #3. Mr. Lyfoung and his family in 1928 at Nong Het, Xieng Khouang, Laos. Mr. Lyfoung was born in 1888 and died on December 12, 1939. He was the son of Mr. Lypao (Ly Dang Pao). Front row, left to right: 1. Touby (3rd son); 2. Tougeu (4th son); 3. Toulia (5th son); 4. Mr. Lyfoung (head of the family), 5. Nang Mao No (daughter, who later was married to Mr. Tou Ly, Gen. Vang Pao’s older brother. After Tou Ly died in a car accident, she remarried with Col. Mua Su, son of Col. Cher Pao Mua. Nang Mao No died in Georgia, USA in 2006.); 6. Kue Choua Lyfoung (Mr. Lyfoung’s 3rd wife, carrying her son Chou, died in 1929); 7. Mr. Lyfoung’s daughter Mao Song (she later became Mrs. Vang Nkaj Zeb. She was the mother of Col. Vang Neng, from France. She passed away in 2006 in the US). Second row, left to right: 1. Ly Chao (first son of Mr. Lyfoung); 2. Yang Tongxeng (brother-in-law, married to Phauj Zuag); 3. Ly Pobzeb (2nd son of Mr. Lyfoung, served as Tasseng, later died falling off a horse saddle; his wife then became his brother Touby’s second wife); 4. Thoj Blia (wife of Mr. Ly Chao); 5. Mrs. Lyfoung, born Yang Va (Mr. Lyfoung’s first wife, died in 1945); 6. Mrs. Tongxeng Yang, nee Mao or Paj Zouag. This picture was taken by Prince Phetsarath during his visit to Xieng Khouang during 1927-1928.

In 1939, the Second World War exploded and then raged in France and throughout Europe. The French suffered heavy casualties and were the obvious losers. As a result, the French troops in Indochina had no real back-up to fight against the Japanese. Many got killed, and the rest sought refuge among their local supporters –especially low-land Lao and Lao Hmong, who put them into hiding in the forest areas. During that war, the Lo Kaitong family chose instead to join the Japanese, the Viet Minh and the Lao Issara in the fight against the French, but ended up being the victims of the Vietminh who were using them. The Lo Kaitong family made that decision because the French had picked the Lyfoung family to lead the Hmong in the Nonghet area in replacement of the Lo family. They wanted to regain their dignity among the Hmong people. Unfortunately, luck was not on their side due to the Vietminh’s ploy.

During 1945-1946, many changes took place as a result of the Japanese occupation. The Ly family, who used to side with the French, had to flee into the jungle with the French troops, who pursued everywhere by the Lao Issara, the Hmong Lo Vietminh, and the Japanese.

Photo # 4. Mr. Lyfoung’s wife and the mother of Phagna Touby Lyfoung (to the left, resting her right hand on the head of a kid) and her three sisters in 1923.

Photo # 4. Mr. Lyfoung’s wife and the mother of Phagna Touby Lyfoung (to the left, resting her right hand on the head of a kid) and her three sisters in 1923.

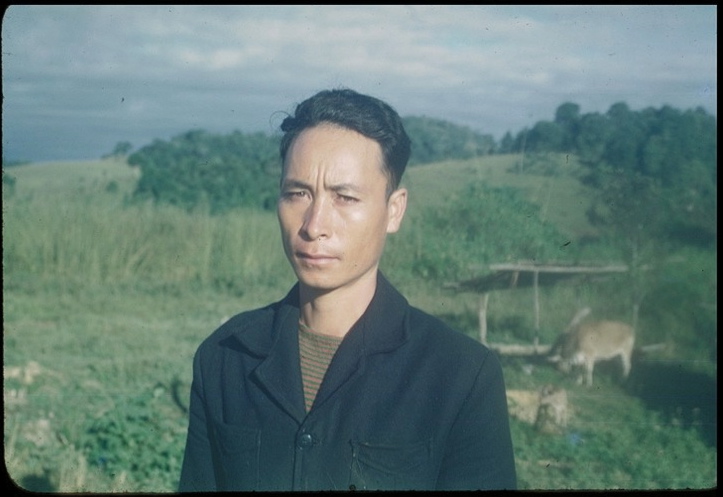

Photo #5. Beechou Lor, who fought the Lao Issara and the Viet-Minh alongside Phagna Touby Lyfoung during 1945-1949.

Photo #5. Beechou Lor, who fought the Lao Issara and the Viet-Minh alongside Phagna Touby Lyfoung during 1945-1949.

Photo #6. Pacha Ly, the leader who, together with Toulia Lyfoung, recruited the Hmong in the Muang Pha and Phasay to recapture Xieng Khouang on January 27, 1946.

Photo #6. Pacha Ly, the leader who, together with Toulia Lyfoung, recruited the Hmong in the Muang Pha and Phasay to recapture Xieng Khouang on January 27, 1946.

During the Second World War, Vang Pao was still a teen-ager of about fourteen years old. Touby, Chao Saykham and the French used Vang Pao as a messenger and informant operating around the mountains of Nonghet and Xieng Khouang. He performed his duties exceptionally well and ended up being a very reliable secret agent. By the time he was eighteen, the French recruited him into the French military service. In 1951, he went to the Army officer training school Dong Hen, Savannakhet Province where he graduated with the rank of aspirant. Vang Pao was a well-behaved cadet, very smart in military tactics, a sharp shooter with excellent health, and a fast runner. One of Vang Pao’s close friends at the Cadet School was Col. Koka Phonsopha, who now resides in North- Carolina.

The Japanese invaded Laos on March 9, 1945. The first atomic bomb hit Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and the second bomb hit Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. Those two dates were especttively August 7 and 10 –Japan’s local time.

The Japanese surrendered to the Allies on August 14, 1945 (August 15 Japan’s time). They withdrew their troops from Indochina, and left behind their arms and ammunitions to the Vietminh, the Lao Issara and the Thai for use in the fight against the French and the English –who used to control several Asian countries for a long time. Another part of their war materials was delivered to the Nationalist Chinese (Kuo-Minh-Tan), who dispatched Division 913 from Yun-Nan to disarm the Japanese. The Lao Issara and the Viet Minh rose up to fight against the French using that equipment.

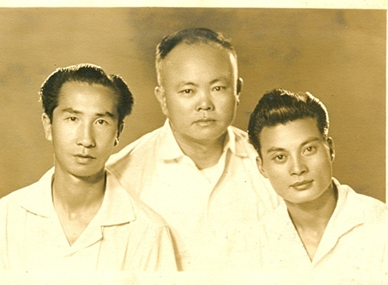

Photo # 7. Tiao Khammanh Vongkot Rattana and his third daughter visited Xieng Khouang between February 25, 1951 and July 3, 1951. From left to right: 1. Touby Lyfoung, 2. Tougeu Lyfoung, 3. Tiao Khammanh Vongkot Rattana (born on May 7, 1889 in Louang Prabang, died on January 22, 1972 in Louang Prabang, Laos; oldest son of Tiao Vongkot andPrincess Rattavadee), 4. Tiao Khamphoui Vongkot (born July 10, 1923 in Louang Prabang, died of old age on December 12, 2002 in Clermont-Ferrand, France at the age of 79; was a Lt. Col. In the Royal Lao Army, Social Service), and 5. Toulia Lyfoung (born on March 14, 1922 in Xieng Khouang, died of old age on October 5, 1996 at Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France at the age of 74; was elected representative of Xieng Khouang Province during 1947-1950, and a member of the legal committee until 1975). Photo taken on February 27, 1951.

Photo # 7. Tiao Khammanh Vongkot Rattana and his third daughter visited Xieng Khouang between February 25, 1951 and July 3, 1951. From left to right: 1. Touby Lyfoung, 2. Tougeu Lyfoung, 3. Tiao Khammanh Vongkot Rattana (born on May 7, 1889 in Louang Prabang, died on January 22, 1972 in Louang Prabang, Laos; oldest son of Tiao Vongkot andPrincess Rattavadee), 4. Tiao Khamphoui Vongkot (born July 10, 1923 in Louang Prabang, died of old age on December 12, 2002 in Clermont-Ferrand, France at the age of 79; was a Lt. Col. In the Royal Lao Army, Social Service), and 5. Toulia Lyfoung (born on March 14, 1922 in Xieng Khouang, died of old age on October 5, 1996 at Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France at the age of 74; was elected representative of Xieng Khouang Province during 1947-1950, and a member of the legal committee until 1975). Photo taken on February 27, 1951.

In 1946, the Lao Issara and the Hmong Lo troops were wiped out by the French, and had to seek refuge in Thailand and in areas along the Vietnam/Laos border, first in Sayabouri Province and later in Champassack Province. That same year, the French forced Thailand to return those two provinces back to Laos. The Lao Issara then escaped to Phongsaly Province, in northern Laos, and to Nge-Anh Province, along the North-Vietnam/Laos border, north of Yiep Son. During 1945-1954, the French emerged from the German occupation and started showing renewed interest in the Lao and Lao Hmong ethnics. This was an opportunity for France to regain power and a sizeable amount of natural resources that were lost during the armed conflicts. Besides, France still considered Indochina as its colonial territories and wished to come back and reenergize the economy of those naturally rich territories to help reshape its own economy.

In September 1945, the French started flying military equipment from Calcutta, India to Laos and dropped it from the air to spots where their troops were still in the hiding. Hiding spots included several southern Lao provinces led by Prince Boun Oum Na Champassak, Louang Prabang Province led by Tiao Kindavong, and Xieng Khouang and Houaphan Provinces led by Chao Saykham, Touby Lyfoung and Chong Toua Moua. As mentioned earlier, the fight against the Lao Issara and the Vietminh in the Nonghet and Xieng Khouang areas made Lao Issara leader Phoumi Vongvichit unhappy with the French, Lao and Hmong leaders because they had captured Phagna Muang Khoua, Khamlek (the brother of the national head monk Bounthan and the father of Dr. Khamsengkeo Sengsathit) and summarily executed him.

Photo #8 . Chaokhoueng Chao Saykham Soukthaka Koumane (born in 1918, immigrated to France and died in Perpignan; fought the war against the Viet-Minh together with Touby Lyfoung and against the Vietnamese communists with Gen. Vang Pao during 1960-1975 before immigrating to France; a real Phuan prince who loved his family, his people and his country, and did a lot for the Hmong population – see his biography 5.5.1).

Photo #8 . Chaokhoueng Chao Saykham Soukthaka Koumane (born in 1918, immigrated to France and died in Perpignan; fought the war against the Viet-Minh together with Touby Lyfoung and against the Vietnamese communists with Gen. Vang Pao during 1960-1975 before immigrating to France; a real Phuan prince who loved his family, his people and his country, and did a lot for the Hmong population – see his biography 5.5.1).

Photo #9 . Touby Lyfoung (born in 1919, died of an agonizing death at the Vieng Xay re-education camp, Houaphan Province). Both Chao Saykham and Touby Lyfoung were Lao leaders who fought the Lao Issara and the Viet-Minh alongside the French during 1945-1954. Phagna Touby never left the country – see his biography 5.5.2

Photo #9 . Touby Lyfoung (born in 1919, died of an agonizing death at the Vieng Xay re-education camp, Houaphan Province). Both Chao Saykham and Touby Lyfoung were Lao leaders who fought the Lao Issara and the Viet-Minh alongside the French during 1945-1954. Phagna Touby never left the country – see his biography 5.5.2

Toulia Lyfoung Headed to Louang Prabang to Release the King

In December 1945, Tou Lia and Pa Cha Ly mobilized around 300 Hmong in Navang and Phou Phaxay regions (south of Xieng Khouang Province) and gave them basic military training. During the mobilization and training, one company of the Lao Issara and Viet Minh moved in to attack Sane Ho, but got ambushed by a platoon of Hmong. Because the Hmong were only armed with shot guns, the outcome was not as good as expected. Later on, Tou Lia and Pa Cha Ly took the 300 or so armed Hmong to join hands with Touby and Chao Saykham in the successful liberation of Xieng Khouang. From there, they gathered a 600 Hmong contingent and headed out to the Plain of Jars, Muang Soui, Phou Vieng, and Sala Phou Khoune. From Sala Phou Khoun, the original contingent was split into two groups of 300 people each.

The first group took Highway 13 to Luang Prabang, led by Tou Lia. Its mission was to release the King who was confined at the royal palace by the Lao Issara. By the time Tou Lia and his troops were about to reach Louang Prabang, the Lao Issara had already left town. This first contingent then provided security surveillance and protection for the king. The second contingent, led by Pa Cha Ly, followed Highway 13 in the other (southward) direction heading toward Kasy, then followed the high mountain trail to Muang Phoune and Vang Vieng. Its mission was to help liberate the capital city of Vientiane, which was then under Lao Issara’s control. When they arrived in Vang Vieng, they had a quick fight with Lao Issara soldiers and were ordered to pull back. By the time they reached Muang Phoune, on April 25, 1946, the Lao Issara had already left Vientiane.

Photo # 10. Mrs. Touby Lyfoung, her children and relatives. Front row boys: 1. Touvu Lyfoung, 2. Touxa Lyfoung, 3. TouXoua Lyfoung, and.4. Toulong Lyfoung. Back row: 5. Lyvang Lyfoung, 6. LyXu Lyfoung, 7. Lykhoua Lyfoung. Girls: 8. Gaoly Lyfoung (on her mom’s arm), 9. Mrs. Touby Lyfoung (born Song Yang Tongseng), 10. Tiao Khamphoui Vongkotratana, third daughter of Tiao Khammane Vongkot Rattana and sister of Tiao Khampheng Vongkot Rattana, former wife of Toulia Lyfoung), 11. unknown, 12. Mao SongYang, and 13. Nang Song. The photo was taken in front of the residence of Mr. Touby Lyfoung in Xieng Khouang in February 1951.

Photo # 10. Mrs. Touby Lyfoung, her children and relatives. Front row boys: 1. Touvu Lyfoung, 2. Touxa Lyfoung, 3. TouXoua Lyfoung, and.4. Toulong Lyfoung. Back row: 5. Lyvang Lyfoung, 6. LyXu Lyfoung, 7. Lykhoua Lyfoung. Girls: 8. Gaoly Lyfoung (on her mom’s arm), 9. Mrs. Touby Lyfoung (born Song Yang Tongseng), 10. Tiao Khamphoui Vongkotratana, third daughter of Tiao Khammane Vongkot Rattana and sister of Tiao Khampheng Vongkot Rattana, former wife of Toulia Lyfoung), 11. unknown, 12. Mao SongYang, and 13. Nang Song. The photo was taken in front of the residence of Mr. Touby Lyfoung in Xieng Khouang in February 1951.

When he got back to Xieng Khouang, Say Pao Vang, commander of the recruits from Muang Pha and Phou Pha Say said, “Only an educated person can be a leader. I know that because I don’t have an education and am having problem doing anything. I was scared when Phagna Touby made me a military commander.” For that reason, in February 1947, he moved to Dong Dane (near Lat Houang, not too far from Xieng Khouang) with his children and younger brothers so they could attend school. [The author was one of those who started school in 1947]. They were part of the very first Hmong family in Xieng Khouang Province to get a chance to learn about Jesus Christ, a Christian family that led many others to convert to Christianity.

Photo #11. The first Team Hmong Leaders First Row, left to right: 1. Tswv Choj Lis (Nai ban Phakvene); 2. Txiajvaj Xyooj (Tasseng Phousane Noi); 3. Ntsuab Txos Xiong (tasseng Phou Phaxay); 4. Suavtuam Lis (tasseng Keng Khoui ). -Second Row, left to right: 1. Neejtswb Vaj (Gen. Vang Pao’s father, Photong Nong Het ); 2. Txiajvaj Xyooj (Tasseng Phak Leung); 3. Paj Lwj Lee (Photong Phak Boun); 4. Nomyis Yang (Tasseng Phou Fa); 5. Txoovtuam Muas the first Hmong Naikong Phoudou). -Third Row: left to right: 1. Phagna Damrong Rithikay Touby Lyfoung; 2. Ly Chao Lyfoung; 3. Tiao Khammane Vongkot Ratana; 4. Xaiv tshob Yang (Naiban Hine Tang); 5. Nchaiv Pov Vang (Tasseng Na Vang); 6. Lao Officer; and 7. Toulia Lyfoung.

Photo #11. The first Team Hmong Leaders First Row, left to right: 1. Tswv Choj Lis (Nai ban Phakvene); 2. Txiajvaj Xyooj (Tasseng Phousane Noi); 3. Ntsuab Txos Xiong (tasseng Phou Phaxay); 4. Suavtuam Lis (tasseng Keng Khoui ). -Second Row, left to right: 1. Neejtswb Vaj (Gen. Vang Pao’s father, Photong Nong Het ); 2. Txiajvaj Xyooj (Tasseng Phak Leung); 3. Paj Lwj Lee (Photong Phak Boun); 4. Nomyis Yang (Tasseng Phou Fa); 5. Txoovtuam Muas the first Hmong Naikong Phoudou). -Third Row: left to right: 1. Phagna Damrong Rithikay Touby Lyfoung; 2. Ly Chao Lyfoung; 3. Tiao Khammane Vongkot Ratana; 4. Xaiv tshob Yang (Naiban Hine Tang); 5. Nchaiv Pov Vang (Tasseng Na Vang); 6. Lao Officer; and 7. Toulia Lyfoung.

Tou Lia wrote in his Memoirs, “The recruitment of the Hmong for the fight against the Lao Issara and the Vietminh this time allowed the Hmong to get to know each other a lot better, and made them feel they are part of the same unified ethnic group. This is different from the past, when the Hmong first emigrated from Mainland China to resettle in Laos. They then did not know each other, lived in small groups, and made little progress in thinking and ideology. But once they were involved in a common fight, the Hmong and the Lao collaborated better with each other, and appreciated each other more.”

HO Chi-Minh

When the Lao Issara fought against the French, Laos was still a French protectorate. This led to the creation of two factions or two political parties as follows:

- The Lao Issara led by Prince Phetsarath, the loosing faction, and

- The Pro-French faction with several leaders from north to south, the faction with an edge in the fight against the Lao Issara and the Vietminh.

In Vientiane, Prince Phetsarath was the leader who set up the government and, on October 12, 1945, named Phagna Khammao Vilay as Prime Minister of an 11-member Cabinet. See Chapter on Government Formation. He issued a proclamation dismissing King Sasavang Vong from the throne.

By the end of 1945, in the war that raged between the two sides across Laos, the Lao Issara side ended up being the loosers, compelling one of its groups to retreat across the Mekong River into Thailand. While crossing the Mekong River on a boat in the Thakhek area, Prince Souphanouvong got seriously injured by gunfire from a French fighter plane. The Vietnamese living in Thailand were able to help him escape from danger. After he recovered from his injury, Prince Souphanouvong reported back to his boss Ho-Chi-Minh in North-Vietnam, along with the following Issara party members: Phoumi Vongvichit, Soth Phetlasy, Keo Viprakorn, Nouhack, Kaysone Phomvihan, Quinim Pholsena, Fay Dang Lo, Lo Foung, and a few others. Another Lao Issara group went back to Vientiane to join hands with the Royal Lao Government.

The government structure in Vietnam under the French regime was similar to the government structure in place in Laos. The French put Prince Nguyen Vinh Thuy, the son of the former emperor, on the throne under the name of Emperor Bao-Dai. They also divided the country into three regions for easier administrative control–Tonkin (North-Vietnam), Annam (Central-Vietnam), and Cochinchine (South-Vietnam). There were indeed plenty of reasons why the people of Indochina chose to fight against the French.

Ho Chi Minh (alias Nguyen Ai Quoc), according to known sources, was born in 1890 and died on July 20, 1969 in Hanoi, North-Vietnam. He studied Communism in France and traveled to Russia in 1927 for further studies. He went to Thailand in 1928, traveled to Oudorn Thanee, Sakon Nakhorn, and Nakhorn Phanom, and stayed in hiding in the village of Ban Na Chok, motivating Vietnamese residents to rise up to help recover independence from France. At that time, Thailand was implementing a policy different from France’s policy.

In 1931, Nguyen Ai Quoc went to Hong-Kong to contact North-Vietnamese residents but was arrested by the English authorities who arrested and put him into jail. To reduce French pressure for extradition, the British fakely announced in 1932 that Quoc had died. They then quietly released him in January 1933. In 1934, Nguyen Ai Quoc went back to Russia and, starting around 1940, began regularly using the name “Ho-Chi-Minh”. In 1941, he returned to North-Vietnam to work with the Thai Nong, Thai Dam, Thai Khao, and Hmong ethnics in seeking military support from the US for the fight against the Japanese. But the weapons he got were used against the French instead, in an effort to free Vietnam from the French domination. The French then were faced with many challenges due to the Second World War.

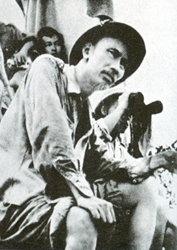

Photo#12 . Ho Chi Minh (born in 1890, died on July 20, 1969 in Hanoi, North-Vietnam) went secretly aboard a French ship on the way to France where he completed his communism training. On this picture, he was observing and planning how to wipe out the French’s positions in Dien Bien Phu, in March 1954.

Photo#12 . Ho Chi Minh (born in 1890, died on July 20, 1969 in Hanoi, North-Vietnam) went secretly aboard a French ship on the way to France where he completed his communism training. On this picture, he was observing and planning how to wipe out the French’s positions in Dien Bien Phu, in March 1954.

Photo#13 . Kaysone Phomvihane had met with Ho Chi Minh earlier in 1951.

Photo#13 . Kaysone Phomvihane had met with Ho Chi Minh earlier in 1951.

In 1945, Ho Chi Minh and the Lao Issara began to form national liberation fronts. On August 15, 1945 Ho-Chi-Minh led armed attacks on several French positions in Vietnam. On August 27, 1946 situational changes made it possible for France to regain power in Indochina. This forced Ho-Chi-Minh, along with Vietminh and Lao Issara troops, to flee to the jungle and start guerilla operations. These operations expanded by the day and caused the French to use military forces to fight the Vietminh and the Lao Issara. The fighting unavoidably caused losses of lives and material damages and, as a result, increased Vietnamese resentment and their hate for the French.

In 1949, China went from a democratic regime to a communist regime, from Chiang Kai-Shek to Mao Zedong. In 1950, war erupted in Korea between the western and the eastern powers, including mainland China which supported North-Korea. In 1950, fighting in Indochina intensified and gave an opportunity for Ho-Chi-Minh to decide to join the camp of communist mainland China and use the China-Vietnam-Laos border area as training centers for the Vietminh. This development caused serious concern to the French and US governments about the growth of the communism which could potentially spread over other parts of south-east Asia. The French and the US then decided to set up the Dien-Bien-Phu military base to counter communist expansion, along with other programs as follows:

- In Phongsaly Province, set up the garrisons of Muang Khoua and Muang Ngoy, under the command base of Nam Bak, Louangprabang Province, and

- Establish thousands of grass-root, village level armed guards in preparation for the fight against the Vietminh in North-Vietnam. Recruits were to include several ethnic groups, including especially Hmong (under Vang Chong’s command), Thai Dam (under Deo Van An’s command), Thai Khao and North-Vietnamese.

Photo #14. The group that fought the war against the Lao Issara and Viet Minh, 1945-1954. From left to right: front row: 1. Paj Lwj Lis, 2. Neej Tswb Vaj, 3. Touby Lyfoung, 4. Nom txos Lyfoung, 5. Ly Xiong, 6. Tsuab Txos Xyooj. Second row: 1. Ntsuab Pov Yang, 2. Ntxoov Vws Tsab, 3. Lis Vaj Tooj Pov, 4. Tswv Choj Lis , 5. Xaiv Tshob Yang, 6. Txiaj Xab Mua, 7. Nom Yis Yang, 8. Suav Tuam Lis, 9. Txiaj Vaj Xyooj, 10. Tooj Kais Xyooj (Tasseng Phou Sane Noi). This photo was taken in 1948 in Xieng Khouangwhen Phagna Touby Lyfoung was appointed the first Hmong district chief in Laos.

Photo #14. The group that fought the war against the Lao Issara and Viet Minh, 1945-1954. From left to right: front row: 1. Paj Lwj Lis, 2. Neej Tswb Vaj, 3. Touby Lyfoung, 4. Nom txos Lyfoung, 5. Ly Xiong, 6. Tsuab Txos Xyooj. Second row: 1. Ntsuab Pov Yang, 2. Ntxoov Vws Tsab, 3. Lis Vaj Tooj Pov, 4. Tswv Choj Lis , 5. Xaiv Tshob Yang, 6. Txiaj Xab Mua, 7. Nom Yis Yang, 8. Suav Tuam Lis, 9. Txiaj Vaj Xyooj, 10. Tooj Kais Xyooj (Tasseng Phou Sane Noi). This photo was taken in 1948 in Xieng Khouangwhen Phagna Touby Lyfoung was appointed the first Hmong district chief in Laos.

Photo#15. Naikong Chong Toua Mua and Sergent Haze, a Frenchman of German descent and a farmer at Phou Dou after his discharge from the French Army stationed at the Khang Khay Camp. He was a close friend of the Naikong of Phou Dou and was active in supplying vegetables to the French troops in Khang Khay. Naikong Chong Toua died in early 1952 by car accident, due to his lack of car driving experience.

Photo#15. Naikong Chong Toua Mua and Sergent Haze, a Frenchman of German descent and a farmer at Phou Dou after his discharge from the French Army stationed at the Khang Khay Camp. He was a close friend of the Naikong of Phou Dou and was active in supplying vegetables to the French troops in Khang Khay. Naikong Chong Toua died in early 1952 by car accident, due to his lack of car driving experience.

Photo # 16. From left to right: Tasseng Say Pao Vang, Chay Dang Vang and Col. Cher Pao Mua.Say Pao Vang was the one whoasked Phagna Touby not to retreat from Xieng Khouang on January 26, 1946. Col. Cher Pao Mua was the commander of LS 32 at Bouam Long with no less than 12,000 soldiers attached to Regiment 28. He immigrated with his family to Thailand as a refugee but refused to leave his troops behind. He went back to fight in Laos where he died in 1994.

Photo # 16. From left to right: Tasseng Say Pao Vang, Chay Dang Vang and Col. Cher Pao Mua.Say Pao Vang was the one whoasked Phagna Touby not to retreat from Xieng Khouang on January 26, 1946. Col. Cher Pao Mua was the commander of LS 32 at Bouam Long with no less than 12,000 soldiers attached to Regiment 28. He immigrated with his family to Thailand as a refugee but refused to leave his troops behind. He went back to fight in Laos where he died in 1994.

Other Leaders from North-Vietnam

During 1951-1954 French war in Indochina, fierce fighting occurred between the French and the communist troops. In the end, France lost Indochina and created thousands of refugees (most of them educated people) who had to leave North-Vietnam to resettle in Laos, Thailand and France. Lt. Vang Chong, a Hmong leader, was one of those who had to leave North-Vietnam to resettle in Laos. Lt. Vang Chong was a Hmong leader who left North-Vietnam and resettled in Laos.

Photo #17. Lt. Vang Chong, a Hmong leader in Dien-Bien-Phu in 1952. He immigrated to Laos in 1955 and died of illness at Long Cheng in 1973.

Photo #17. Lt. Vang Chong, a Hmong leader in Dien-Bien-Phu in 1952. He immigrated to Laos in 1955 and died of illness at Long Cheng in 1973.

Photo # 18. Mr. Deo Van An, a Thai Dam leader in Dien-Bien-Phu in 1954. He immigrated to France in 1955.

Photo # 18. Mr. Deo Van An, a Thai Dam leader in Dien-Bien-Phu in 1954. He immigrated to France in 1955.

Photo # 19. Thai Khao Leaders (from left to right): Ong Sang, Ong Dzeng and Ong Dzin

Lt. Vang Chong was born in August1919 in Ban Houei Xane, Tasseng Dien-Bien-Phu in the Province of Lai Chau, North-Vietnam. He died in Laos’ Military Region II at Long Cheng, Xieng Khouang Province in April 1973. When Vang Chong was ten years old, his uncle Liaj Vam Vang sent him to school at Dien-Bien-Phu where he lived with the family of one of his uncle’s friend, a Thai Dam native, to be closer to school. In 1936, his uncle Dang Seng Vang, a district chief, pulled him out of school to perform some record filing work, as his secretary was not experienced enough in that area.

In 1944, French Maj. Imfeld nominated Vang Chong to be the deputy-Chaomuang of Dien-Bien- Phu and exercise administrative control over some 18,000 Thai Dam, LaoTheung, Hmong and Thai Khao. In 1945, Vang Chong was arrested by the Japanese and detained for about a month. The Japanese wrote to District Chief Dang Seng Vang to ask him to collect three thousand silver coins as bail payment for Vang Chong’s release. This was right before the atomic bombs hit Japan. As a result of those incidents and the Japan’s surrender, Vang Chong was released from prison without having to pay anything. Later that year, deputy-district chief Vang Chong led a group of forty Hmong to Yunan Province in southern China to look for French families who sought refuge there during the Japanese occupation and bring them back to the French garrison of Lai Chau, North-Vietnam and set up the Dien-Bien-Phu military base.

In November 1947, two companies of Thai Khao troops attacked many Hmong villages and burned them down. The French were not able to do anything to prevent this type of attack. Therefore, Vang Chong felt compelled to lead Hmong troops to mount a revenge attack against the Thai Khao. In December 1949, the French ordered the Hmong to resettle in Muang Khoua, Phong Saly Province in northern Laos, and get ready to support the French in their fight against the Vietminh. The Muang Khoua garrison was then under the command of Capt. Vigauche.

By the end of 1950, the French had Vang Chong and several Hmong soldiers take a two-month military training. Once the training was completed, Vang Chong was promoted to the rank of Sergeant, put in command of a Hmong company, and deployed to the garrison of Ban Anh, Muang Ngoy, close to the Nam Bark garrison. His assignment was to secure the area around Nam Bark and protect the northern part of Laos. Sergeant Vang Chong was a very well-disciplined commander who knew how to fight, judging from the hundreds of enemy troops he put out of action and the sizeable amount of arms and ammunitions he was able to collect. He got a citation from the Muang Khoua French commander and, based on his outstanding achievements, was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant and deployed to the Muang Khoua garrison to clear the Vietminh from the banks of the Nam Ou River.

In August 1953, Capt. Mason invited Touby Lyfoung to visit Lt. Vang Chong and his troops at Muang Say. The French also promised to send a radio dispatcher and a nurse to assist Lt. Vang Chong’s troops and get them ready to suppor the French base of Dien-Bien-Phu. All these promises were fulfilled. In February 1954, Vang Chong advanced his troops toward Dien-Bien-Phu. As they were 30 kilometers way from the Camp, many problems arose, including gradually intensified attacks from the Vietminh, and diminishing food supply and ammunitions. He had the radio dispatcher send a message to the Dien-Bien-Phu commander but got no replies. Not a single supply airplane in sight. This was close to the end of February. Vang Chong had no choice but to order a 40-kilometer retreat, and wait for airplanes to drop them some supplies. The retreat was painful, with the enemy on their tail every step of the way, and the Hmong troops running out of ammunitions.

Before Lt. Vang Chong began to move his troops toward Dien Bien Phu, he has about thirty of his men sent to Saigon/Ho-Ch-Minh City, South Vietnam for parachute training. Although these men had not yet completed the training, the French dropped them off at Dien Bien Phu. All thirty of them were killed while still floating down on their parachutes. Because they had access to state-of-the-art anti-aircraft weapons, the Vietminh were also able to shoot down several French airplanes.

French officers operating in the Dien-Bien-Phu area in North-Vietnam since 1937 included S/Lt. Navan, S/Lt. Beagent, Maj. Imfill, Maj. Delling, and Maj. Salan. A few others were there even earlier. Those stationed in the Phongsaly area in Laos at the same time as Lt. Vang Chong included Lt. Vally, Capt. Vigauche, Major Fournier, Capt. Mason (GCMA), and Gen. Rene Cogny (who provided the names of the officers to Lt. Vang Chong). During his fights in northern Laos, Lt. Vang Chong got citations from the French and King Sisavangvong. He decided to resettle in Laos in 1955.

Photo #20. Lt. Vang Chong’s troops about to be dropped by parachutes to Dien-Bien-Phu (where they all got killed).

Photo #20. Lt. Vang Chong’s troops about to be dropped by parachutes to Dien-Bien-Phu (where they all got killed).

The preceding paragraphs were excerpted from the notes recorded by Maj. Nao Chue Vang, son of Lt. Vang Chong, who resetlled in Laos and participated in the 1960-1975 fight alongside Gen. Vang Pao and the US. Maj. Nao Chue Vang noted that his father and his uncle, Liaj Vam Vang, told him the Dien-Bien-Phu war was a modern age battle that used airplanes and fire-arms that were never seen before, a very scary episode indeed. This war led more than 40,000 refugees to resettle in Laos and eastern Thailand in 1954. These were Hmong who used to live in the following provinces of northern Vietnam: LaiChau, Laokay, Hazang, Dien Bien Phu, and Songla. [Note from the author: My personal thanks to Major Nao Chue, a high-ranking officer in the Royal Lao Army during 1960-1975, for sharing his personal notes.]

Photo #21. ImportantThai Khao leaders who fought alongside the French during 1950-1954 and resettled at Lat Houang, Xieng Khouang Province. From left to right: Lt. Nguyen Dinh Tan (died in Toul, France), Lt. Pham Van Duon (immigrated to Metz, France where he died in 1980), and an unknown officer. Several thousand of refugees from different ethnic groups in North-Vietnam resettled in the Lao provinces of Xieng Khouang, Sayabouri, Vientiane and Savannakhet.